Because reading a poem is one of our superpowers.

If I could write one of these Substacks every day I could easily do a month of Sunday poems. Just off the top of my head, there are the “Sunday Morning”s of Wallace Stevens and Louis MacNeice, Robert Hayden’s “Those Winter Sundays” and Emily Dickinson’s “Some keep the Sabbath going to Church – (236).” Even in D.H. Lawrence’s “Piano,” “the old Sunday evenings at home” continue to exert a mysterious power over the heart of the now long-grown child. What Sunday is, and is for, is one of poetry’s Stammgäste (regulars).1

I suspect all these poems have got George Herbert’s “Prayer I” in their rearview mirrors. Herbert calls the act of prayer “[t]he six-days world transposing in an hour.” The prayer and the hour are both synecdoches (the part standing in for the whole)2 for Sunday. It’s Sunday that has the power to place the more mundane, prosaic parts of life in a larger setting, playing them in a different register or key, altering the terms of the equation.3 Sunday doesn’t erase the six-days world or the effects it has on us, but it can imbue them with spirit and significance, coloring how we feel about them and what they come to mean.

Whether we number ourselves among Dickinson’s Some or her implied Others, the idea that Sunday answers a fundamental need endures. When I searched “how to spend Sundays,” the engine returned a volley of imperatives—“Go! Do! Start! Get! Plan! Watch! Make Sure! Clean Up! Spend! Pursue! Prepare!”—and generated pages of resolutely inspiring suggestions: 13 Productive Things To Do on a Sunday, 6 Smarter Ways To Spend Your Sunday, 30+ Entertaining and Refreshing Things To Do on a Sunday. The New York Times proposes Sunday Routine, “featuring a complete archive of columns that chronicle the Sundays of newsworthy New Yorkers, going back to 2009.”

Leafing through these directories of paragons and purpose, the dauntless individual who woke up one fine Sunday looking for some way to make it count might close her laptop and decide to sleep in. I wouldn’t blame her, but I might suggest as an alternative taking a page out of the Sundays of a certain Satin-Legs Smith as portrayed in the poem by Gwendolyn Brooks that bears his name. Warning: it’s longer than a page. Suggestion: Read it out loud — to a plant, or your cat.

The Sundays of Satin-Legs Smith by Gwendolyn Brooks

Inamoratas, with an approbation,

Bestowed his title. Blessed his inclination.

He wakes, unwinds, elaborately: a cat

Tawny, reluctant, royal. He is fat

And fine this morning. Definite. Reimbursed.

He waits a moment, he designs his reign,

That no performance may be plain or vain.

Then rises in a clear delirium.

He sheds, with his pajamas, shabby days.

And his desertedness, his intricate fear, the

Postponed resentments and the prim precautions.

Now, at his bath, would you deny him lavender

Or take away the power of his pine?

What smelly substitute, heady as wine,

Would you provide? life must be aromatic.

There must be scent, somehow there must be some.

Would you have flowers in his life? suggest

Asters? a Really Good geranium?

A white carnation? would you prescribe a Show

With the cold lilies, formal chrysanthemum

Magnificence, poinsettias, and emphatic

Red of prize roses? might his happiest

Alternative (you muse) be, after all,

A bit of gentle garden in the best

Of taste and straight tradition? Maybe so.

But you forget, or did you ever know,

His heritage of cabbage and pigtails,

Old intimacy with alleys, garbage pails,

Down in the deep (but always beautiful) South

Where roses blush their blithest (it is said)

And sweet magnolias put Chanel to shame.

No! He has not a flower to his name.

Except a feather one, for his lapel.

Apart from that, if he should think of flowers

It is in terms of dandelions or death.

Ah, there is little hope. You might as well—

Unless you care to set the world a-boil

And do a lot of equalizing things,

Remove a little ermine, say, from kings,

Shake hands with paupers and appoint them men,

For instance—certainly you might as well

Leave him his lotion, lavender and oil.

Let us proceed. Let us inspect, together

With his meticulous and serious love,

The innards of this closet. Which is a vault

Whose glory is not diamonds, not pearls,

Not silver plate with just enough dull shine.

But wonder-suits in yellow and in wine,

Sarcastic green and zebra-striped cobalt.

With shoulder padding that is wide

And cocky and determined as his pride;

Ballooning pants that taper off to ends

Scheduled to choke precisely.

Here are hats

Like bright umbrellas; and hysterical ties

Like narrow banners for some gathering war.

People are so in need, in need of help.

People want so much that they do not know.

Below the tinkling trade of little coins

The gold impulse not possible to show

Or spend. Promise piled over and betrayed.

These kneaded limbs receive the kiss of silk.

Then they receive the brave and beautiful

Embrace of some of that equivocal wool.

He looks into his mirror, loves himself—

The neat curve here; the angularity

That is appropriate at just its place;

The technique of a variegated grace.

Here is all his sculpture and his art

And all his architectural design.

Perhaps you would prefer to this a fine

Value of marble, complicated stone.

Would have him think with horror of baroque,

Rococo. You forget and you forget.

He dances down the hotel steps that keep

Remnants of last night’s high life and distress.

As spat-out purchased kisses and spilled beer.

He swallows sunshine with a secret yelp.

Passes to coffee and a roll or two.

Has breakfasted.

Out. Sounds about him smear,

Become a unit. He hears and does not hear

The alarm clock meddling in somebody’s sleep;

Children’s governed Sunday happiness;

The dry tone of a plane; a woman’s oath;

Consumption’s spiritless expectoration;

An indignant robin’s resolute donation

Pinching a track through apathy and din;

Restaurant vendors weeping; and the L

That comes on like a slightly horrible thought.

Pictures, too, as usual, are blurred.

He sees and does not see the broken windows

Hiding their shame with newsprint; little girl

With ribbons decking wornness, little boy

Wearing the trousers with the decentest patch,

To honor Sunday; women on their way

From “service,” temperate holiness arranged

Ably on asking faces; men estranged

From music and from wonder and from joy

But far familiar with the guiding awe

Of foodlessness.

He loiters.

Restaurant vendors

Weep, or out of them rolls a restless glee.

The Lonesome Blues, the Long-lost Blues, I Want A

Big Fat Mama. Down these sore avenues

Comes no Saint-Saëns, no piquant elusive Grieg,

And not Tschaikovsky’s wayward eloquence

And not the shapely tender drift of Brahms.

But could he love them? Since a man must bring

To music what his mother spanked him for

When he was two: bits of forgotten hate,

Devotion: whether or not his mattress hurts:

The little dream his father humored: the thing

His sister did for money: what he ate

For breakfast—and for dinner twenty years

Ago last autumn: all his skipped desserts.

The pasts of his ancestors lean against

Him. Crowd him. Fog out his identity.

Hundreds of hungers mingle with his own,

Hundreds of voices advise so dexterously

He quite considers his reactions his,

Judges he walks most powerfully alone,

That everything is—simply what it is.

But movie-time approaches, time to boo

The hero’s kiss, and boo the heroine

Whose ivory and yellow it is sin

For his eye to eat of. The Mickey Mouse,

However, is for everyone in the house.

Squires his lady to dinner at Joe’s Eats.

His lady alters as to leg and eye,

Thickness and height, such minor points as these,

From Sunday to Sunday. But no matter what

Her name or body positively she’s

In Queen Lace stockings with ambitious heels

That strain to kiss the calves, and vivid shoes

Frontless and backless, Chinese fingernails,

Earrings, three layers of lipstick, intense hat

Dripping with the most voluble of veils.

Her affable extremes are like sweet bombs

About him, whom no middle grace or good

Could gratify. He had no education

In quiet arts of compromise. He would

Not understand your counsels on control, nor

Thank you for your late trouble.

At Joe’s Eats

You get your fish or chicken on meat platters.

With coleslaw, macaroni, candied sweets,

Coffee and apple pie. You go out full.

(The end is—isn’t it?—all that really matters.)

And even and intrepid come

The tender boots of night to home.

Her body is like new brown bread

Under the Woolworth mignonette.

Her body is a honey bowl

Whose waiting honey is deep and hot,

Her body is like summer earth,

Receptive, soft, and absolute ...

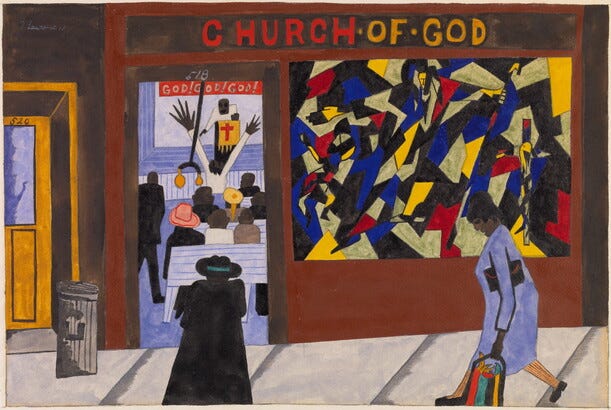

A Street in Bronzeville (1945), Gwendolyn Brooks’s first book, is a tour in poetry of the historic South Chicago neighborhood,4 the early-20th-century center of African-American culture and business where Brooks lived most of her life. There are a number of poems in Bronzeville that give Sunday a sidelong glance, but only two that take the day by the lapels.5

“The Sundays of Satin-Legs Smith” is upfront about what Sunday is for—it’s right there in the title. Sunday, for Satin-Legs Smith, is sartorial: it’s for dressing up.6 On Sunday our eponymous hero breaks open the “vault” of “wonder-suits” he keeps locked away the rest of the week—what you might call his Mr Smith days—and chooses the “yellow” or the “wine,” the “zebra-striped cobalt” or “sarcastic green,” slips on one of his “hysterical ties,” and becomes… Satin-Legs!

For me, the main attraction of superhero narratives has always been how openly, to us, the audience, anyway, their protagonists juggle their separate identities. It’s easier when you only have two, and each is somewhat two-dimensional, but that’s why it works. We never learn what Satin-Legs Smith does the rest of the week, but when he transforms into his Sunday superhero self, it’s not to fight crime, but to make love.

Love is in the air from the very first syllables. “Inamoratas” is one of those words that, like your immigrant grandmother, hasn’t assimilated. Maybe also like her, at the heart of it is amor, the Latin for love. (Capitalized, it becomes the name of the Roman god of love himself.)7

But Satin-Legs Smith doesn’t just dress for the ladies. When he changes into his snazzy Sunday best, “[h]e sheds, with his pajamas, his shabby days. / And his desertedness, his intricate fear, the / Postponed resentments and the prim precautions.” Sunday is the day Satin-Legs Smith “looks into his mirror, loves himself.”

This is not the self-love of the narcissist whose love, it’s worth remembering, is not just inappropriate and excessive but perversely and intractably fixated on getting what he can’t have8. Satin-Legs Smith sees and loves himself approvingly, judiciously: “the neat curve here; the angularity / That is appropriate at just its place.” When he puts on one of his “brave and beautiful” wonder-suits from “the innards of his closet” it’s to claim what by rights ought to be his, the prerogative to be seen by the world, in a way that is not “vain or plain,” for the "brave and beautiful” self he is, inside and out. It’s a self that encompasses his “cocky and determined… pride” and his “meticulous and serious” sensibility, the outsized, Falstaffian appetites and the gourmand’s lust for life they form a part of. Satin-Legs’s self-love is his superpower. It’s what allows his deservedness to reverse the “desertedness”9 that haunts him the rest of the week. It’s what frees him to give expression to the parts of him that, were it not for Sundays, would never see the light of day, but that, thanks to Sunday, turn Satin-Legs Smith into a poem.

Self-love is what quickens Satin-Legs’s sense of what he does, and does not, deserve. But what he, his family and his ancestors have and haven’t deserved in the past decides what he can, and cannot, love:

Since a man must bring To music what his mother spanked him for When he was two: bits of forgotten hate, Devotion: whether or not his mattress hurts: The little dream his father humored: the thing His sister did for money: what he ate For breakfast—and for dinner twenty years Ago last autumn: all his skipped desserts.

(There’s the echo of that ghost again, like a literal-minded opposite of just desserts.10)

This is one of the ways the poem pushes back against its readers’ assumptions— that they are in a position to judge his taste and his predilections, that they are in possession of the kind of help Satin-Legs needs.

Did you also notice that once Satin-Legs dances down the hotel steps into the street the poem stops talking to you altogether? That you only come back toward the very end of the poem?11

The “you” who make up Brooks’s audience are not merely the literal outsiders she escorts on her poet’s tour of her Stammtisch and stomping ground. “You” are also the readers who appraise poetry according to their categories of beauty and fashion. In the context of this poem, this is the aesthetic establishment, whose preferences for perfume run to English estates—“a bit of gentle garden in the best / Of taste and straight tradition,” and who “think with horror of baroque, / Rococo”—who forget, in other words, that beauty is a broad church. First addressing the “you” when Satin-Legs is “at his bath,” the poem immediately makes them an intimate part of the world of the poem, reminding us that it’s something that they—that we—already assuredly are.12

So when the poem catches this “you” judging its hero, it kindly but pointedly admonishes, “But you forget, or did you ever know, / His heritage of cabbage and pigtails, / Old intimacy with alleys, garbage pails, / Down in the deep (but always beautiful) South…. You forget and you forget.”

The act of remembering is a kind of seeing. I think of it as x-ray vision: it looks through what’s in front of its eyes into the past, causes, conditions, contradictions. It’s the kind of seeing we mean when we talk about feeling seen. It’s this kind of seeing, powered by the imagination and paired with empathy, another word for which is love, that is poetry’s superpower.

One of poetry’s jobs is to remind us to remember what seeing is, and is for. To appreciate "all his sculpture and his art,” we need to remember what has made Satin-Legs Smith who he is, and also what has made us who we are.

The poem, a portrait of a man, an x-ray as well as a likeness, offers us the opportunity to see his world through his eyes as well as our own. Like us, “[h]e sees and does not see

the broken windows Hiding their shame with newsprint; little girl With ribbons decking wornness, little boy Wearing the trousers with the decentest patch, To honor Sunday; women on their way From “service,” temperate holiness arranged Ably on asking faces; men estranged From music and from wonder and from joy But far familiar with the guiding awe Of foodlessness.

We could talk about those “broken windows / Hiding their shame with newsprint” for a long time, and it would accommodate every gloss we could come up with. Satin-Legs Smith may not be political, but his poem, an invitation to its guests to try to understand a man, a neighborhood, a world, that is not one of theirs, from the inside, is.

In one of my favorite lines of the poem, Satin-Legs’s artistry is described as “[t]he technique of a variegated grace.” The word variegated, “to make of various sorts or colors,”13 is one of the poem’s many reminders that it speaks to the African-American experience.14 If the Street of the title is a synecdoche for Bronzeville, Bronzeville is also a synecdoche for a larger whole of which it is a representative part. It's also a reminder that there’s no single, wholesale, totalizing, definitive embodiment of that experience. It’s a variegated one. Brooks has written a whole book of poems about it. She will go on to write many others.

The line also speaks to what happens when Satin-Legs Smith dons one of his bright, multicolored, Sunday wonder-suits. He transposes the black-and-white world outside his front door, and the wary, aggrieved, lonely, fearful life he leads in it, into a different key. And yet, for all the vivid, technicolor style he brings to them, his Sundays do not deny that starker world, or that discontented self, any more than they redeem them: even on Sundays, there remains much that “is a sin / for his eye to eat of.”

Like the wool his suits are made of, the Sundays of Satin-Legs Smith are, ultimately, “equivocal.” It’s a synonym for “variegated”—patchwork and patchy. The transpositions of his art can’t lead to anything but a qualified grace. On some level, even Satin-Legs knows it’s just dress-up.

Like Sundays do for Satin-Legs, “The Sundays of Satin-Legs Smith” takes us out of ourselves in a way that takes us into ourselves. Maybe it’s one of the things Sunday is for more generally. “People are so in need, in need of help,” the poem tells us, and then, like an x-ray of that need: “People want so much that they do not know.”15 A few lines later Satin-Legs Smith’s limbs are described as “kneaded.”16 It’s a gentle echo, a gentle reminder that Satin-Legs Smith’s legs are not, of course, literally made of satin, that that’s just another synecdoche17. The condition of his limbs points (by synecdoche again) to the conditions of his life and the source of his needs.

If listicles on the internet are anything to go by, Satin-Legs Smith is not the only one who wakes up once a week searching for a smarter, more productive, entertaining, refreshing and maybe even newsworthy way to end, or begin, the week. We all need help transposing the pummeling of the six-days world that makes up the better, if not the best, part of our collective and individual histories. We all need help kneading18 it into something we can live with, and maybe even for.

That help, according to this poem anyway, seems to have something to do with remembering what we’re forgetting, and learning what it means to see. That’s where Sundays, and poetry, can come in.

See you next “Sunday.”

There really isn’t one English word that does this job. “Regular” (as in customer) takes us to the local bar or pub, but being a Stammgast implies a more complicated habit. It’s more about staying local, feeling grounded. Stamm, from which we get our “stem,” means trunk or tribe and has to do with family and rootedness. A Baumstamm is a tree trunk, but a Stammbaum is a family tree. If you’re a Stammgast you have your Stammtisch, literally your regular, or standing, table, though in fact it’s used more metaphorically, the way some use “peeps,” but see this link for the nuance and more on the family of words that stem from der Stamm. When I try to reverse engineer my choice and search an English translation for Stammgast, bab.la offers me “habitué.” That’s a whole other kettle of poissons.

The kind of substitution synecdoche performs can go the other way, too, the whole taking the place of the part. Here are examples and categories of synecdoche from poetry and everyday speech.

“Transpose.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary, Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/transpose.

Another synecdoche: Street for the people living in the neighborhood and, arguably, Bronzeville for the larger African-American community of the time. Part metaphor, part shorthand, synecdoches are useful for illuminating and obscuring, getting us to see, and keeping us from seeing, both the telling detail and the big picture. There are more coming.

The other, “when you have forgotten Sunday: the love story,” is a love sermon, a modern day “Song of Songs.” It lines Sunday up with poetry and makes spiritual and carnal love, soul and body, metaphors for each other.

There is a growing body of evidence to suggest that this is a tradition that originates in African-American enslaved communities. See, e.g., Lee-Moser, Michelle. "Ever Wondered Why We Say Wear Your ‘Sunday Best’?" LinkedIn, 23 Oct. 2020. https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/ever-wondered-why-we-say-wear-your-sunday-best-michelle-wisdom/; Grelet, Yelena. "The ‘Sunday Best’ Sartorial Tradition: An Explainer." Service95, 3 Apr. 2023, www.service95.com/fashion-sunday-best-tradition/; Howard, Aaron. "There’s a Deep Tradition behind Wearing Your Sunday Best." Jewish Herald-Voice, 2008, https://jhvonline.com/theres-a-deep-tradition-behind-wearing-your-sunday-best-p10854-147.htm.

It also sets the poem going in a way that manages to hearken back to the turn-of-the-last-century Dublin of James Joyce and also hurtle forward to the block parties of the ‘70s: “Inamoratas, with an approbation, / Bestowed his title. Blessed his inclination” reminds me of the opening of Ulysses, which also satirizes conventional religious ritual: "Stately, plump Buck Mulligan came from the stairhead, bearing a bowl of lather on which a mirror and a razor lay crossed." For more on the connections between Brooks and rap, including Kanye West’s account of meeting the poet in the fourth or sixth grade, see St. Felix, Doreen. "Chicago’s Particular Cultural Scene and the Radical Legacy of Gwendolyn Brooks." The New Yorker, 2018, https://www.newyorker.com/culture/culture-desk/chicagos-particular-cultural-scene-and-the-radical-legacy-of-gwendolyn-brooks; Rambsy, Howard II. "Gwendolyn Brooks, Langston Hughes & RapGenius." Cultural Front, 3 Apr. 2013, www.culturalfront.org/2013/04/gwendolyn-brooks-langston-hughes.html; Ferguson, Bernard. "Searching for Gwendolyn Brooks." The Paris Review, 2018, https://www.theparisreview.org/blog/2021/02/16/searching-for-gwendolyn-brooks/.

The love Narcissus bears for himself, in Ovid’s tale, is sterile, self-consuming and self-destructive. A closed system, “he is the seeker and the sought, the longed-for and the one who longs; he is the arsonist—and is the scorched… All that I need, I have: my riches mean my poverty.” (Talk about Stammgast!) Mandelbaum, Allen. The Metamorphosis of Ovid. 1993.

Nonword alert for those of you who have been keeping track since wistlessness et al. in Substack 2.

Maybe it reminds us of other things we each have our own understanding of, and are all entitled to, for example “home," which, according to a character named Mary, we “somehow haven’t to deserve,” from Robert Frost’s “The Death of the Hired Man.” https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/44261/the-death-of-the-hired-man.

Press Control F and look up “you” and see what happens.

If you followed the suggestion in endnote 11, you’ve already noticed the verbs “you” controls from the very first: “deny… take away… provide… have… suggest, etc."

Variegated “comes from the Latin words varius ("various") and agere ("to make, do"). In science, variegation is the occurrence of different colored patches, spots, or streaks in plant leaves, petals, or other parts. This can be due to a lack of pigment or different combinations of pigment in the affected area.” "Variegate." Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 25 Jun. 2023, https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/variegate).

Among the many references to color in the poem, the most explicit are: tawny, lavender, pine, wine, white, red, rose, blush, silver, yellow, wine (again), green, zebra-striped, cobalt, gold, blues, ivory, yellow, coffee, brown, honey, earth.

This line can be read a few ways: People don’t know what it is they want (desire, and also lack). People are so oppressed by their desires and deprivations they are incapable of understanding. It’s also worth noting that those two expansive and compassionate lines about what people need come on the heels of the poem’s quietly ominous reference to “some gathering war.” It’s a veiled acknowledgment—“[d]ripping with the most voluble of veils”—of the limits of prayer, and of poetry. Because if we never strike out into the bigger world that lies beyond the qualified comforts and blind security of our own familiar one, there inevitably comes a time when neither Sunday nor love, and the remembering, and the forgetting, they each make room for, is enough.

As in: pummeled, worked, pounded, squeezed, wrung, twisted, crushed.

Technically, a metonymy, but there’s some overlap.

As in: formed, shaped, molded, mixed, blended.